by Nancy Salvato

Eligibility for POTUS interpreted by SCOTUS

US Schools require students to pass a Federal Constitution test before they graduate from the middle or senior grades. There are multiple opportunities to pass a test that asks students to memorize basic concepts, such as, how a bill becomes a law, the branches of government, checks and balances, and the requirements to hold office, yet, little in depth analysis about the philosophy and history that influenced the Framers is compulsory for students or teachers. Even more unlikely would be to expect them to consider the implications of subsequent legislation and landmark court cases on our interpretation of this document.

and balances, and the requirements to hold office, yet, little in depth analysis about the philosophy and history that influenced the Framers is compulsory for students or teachers. Even more unlikely would be to expect them to consider the implications of subsequent legislation and landmark court cases on our interpretation of this document.

A civic-minded and responsible representative should provide constituents information about proposed bills and an analysis of how the legislation might impact the congressional district. Voters’ opinions about issues should be considered when voting on their behalf. In the real world, there is voter apathy, representatives without an understanding of the founding documents and who do not consider the consequences of ill-considered legislation, and special interests (factions) with unsurpassed influence in Congress. That said, many people would find themselves unable to explain the evolution of the phrase “natural born citizen” or understand or care why it matters.

According to Article II, Section 1 of the United States Constitution, no person except a “natural born citizen” (citizen at birth) shall be eligible to the office of President. Until 1866, the citizenship status of persons born in the United States was not defined in the Constitution or in any federal statute. However, under the common law rule of jus soli — the law of the soil — persons born in the United States generally acquired U.S. citizenship at birth.

Constitutional Convention

John M. Yinger, Trustee Professor of Public Administration and Economics, The Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs, Syracuse  University, and Associate Director for Metropolitan Studies Program and Director, Education Finance and Accountability Program, Center for Policy Research wrote:

University, and Associate Director for Metropolitan Studies Program and Director, Education Finance and Accountability Program, Center for Policy Research wrote:

The delegates at the Constitutional Convention were deeply concerned about foreign influence on the national government, and in particular on the President. .. they wanted the Legislature to select the President, and they tried to limit foreign influence on the President by devising time-of-citizenship requirements for members of the Legislature. Ultimately, however, the Convention decided that a President elected by the Legislature could not be insulated from foreign influence and it turned, instead, to the Electoral College.

In one sense, the switch to the Electoral College lowered the need for explicit presidential qualifications because it minimized the line of potential foreign influence running through the Legislature. In another sense, however, this switch broke the clear connection between the citizenship requirements of legislators and the selection of the President, and therefore boosted the symbolic importance of a citizenship requirement for the President. This change in context, along with the Convention’s decision to make the President the commander-in-chief of the army, gave new weight to the arguments in Jay’s letter, and in particular to the suggestion in that letter that the presidency be restricted to “natural born” citizens.

On March 25, 1800, [Charles] Pinckney made the only documented statement by one of the Founders connecting the Electoral College and the presidential eligibility clause. The Founders “knew well,” he said that to give to the members of Congress a right to give votes in this election, or to decide upon them when given, was to destroy the independence of the Executive, and make him the creature of the Legislature. This therefore they have guarded against, and to insure experience and attachment to the country, they have determined that no man who is not a natural born citizen, or citizen at the adoption of the Constitution, of fourteen years residence, and thirty-five years of age, shall be eligible….

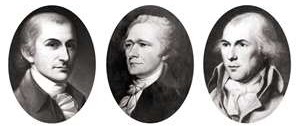

The Federalist Papers

The Federalist Papers (Oct 1787-May 1788) are 85 essays written by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison. Professor Yinger explained that the main focus of essays 2-5, written by Jay, and titled “Concerning Dangers from Foreign Force and Influence” is on

the need for a strong central government to protect a nation from foreign military action, they also suggest that a strong central government can help protect a nation from “foreign influence.” Concern about foreign influence also appears in essay number 20, written by Hamilton and  Madison; essay number 43 by Madison; and essays number 66 and 75 by Hamilton. Moreover, the role of the presidential selection mechanism in limiting foreign influence is explicitly discussed by Hamilton in essay number 68.

Madison; essay number 43 by Madison; and essays number 66 and 75 by Hamilton. Moreover, the role of the presidential selection mechanism in limiting foreign influence is explicitly discussed by Hamilton in essay number 68.

Hamilton said:

Nothing was more to be desired than that every practicable obstacle should be opposed to cabal, intrigue, and corruption. These most deadly adversaries of republican government might naturally have been expected to make their approaches from more than one quarter, but chiefly from the desire in foreign powers to gain an improper ascendant in our councils. How could they better gratify this, than by raising a creature of their own to the chief magistracy of the Union? But the convention have guarded against all danger of this sort, with the most provident and judicious attention. They have not made the appointment of the President to depend on any preexisting bodies of men, who might be tampered with beforehand to prostitute their votes; but they have referred it in the first instance to an immediate act of the people of America, to be exerted in the choice of persons for the temporary and sole purpose of making the appointment. And they have excluded from eligibility to this trust, all those who from situation might be suspected of too great devotion to the President in office. No senator, representative, or other person holding a place of trust or profit under the United States, can be of the numbers of the electors.

St. George Tucker’s “Treatise on the Constitution”

A law professor in the University of William and Mary, a judge of The General Court in Virginia, St. George Tucker also served as a major in the Revolutionary War and was present at the Battle of Yorktown. Yinger cites Tucker’s “Treatise on the Constitution” (1803) as lending further evidence to the link between the natural-born citizen clause and foreign influence.

The Federalist Papers do not mention the issue of presidential qualifications. However, a well-known treatise on the Constitution published in 1803, like Charles Pinckney’s statement in the U.S. Senate in 1800, explicitly discusses the linkage between the “natural born citizen” clause and  the need to avoid foreign influence. In particular, this treatise says:

the need to avoid foreign influence. In particular, this treatise says:

That provision in the constitution which requires that the president shall be a native-born citizen (unless he were a citizen of the United States when the constitution was adopted,) is a happy means of security against foreign influence, which, wherever it is capable of being exerted, is to be dreaded more than the plague. The admission of foreigners into our councils, consequently, cannot be too much guarded against; their total exclusion from a station to which foreign nations have been accustomed to, attach ideas of sovereign power, sacredness of character, and hereditary right, is a measure of the most consummate policy and wisdom. It was by means of foreign connections that the stadtholder of Holland, whose powers at first were probably not equal to those of a president of the United States, became a sovereign hereditary prince before the late revolution in that country. Nor is it with levity that I remark, that the very title of our first magistrate, in some measure exempts us from the danger of those calamities by which European nations are almost perpetually visited. The title of king, prince, emperor, or czar, without the smallest addition to his powers, would have rendered him a member of the fraternity of crowned heads: their common cause has more than once threatened the desolation of Europe. To have added a member to this sacred family in America, would have invited and perpetuated among us all the evils of Pandora’s Box.

Laws of Nature

Federalist Blog author, P.A. Madison, factors in President Washington’s admonition about foreign attachment when formulating what the Founders and Framers meant by natural-born citizen. Our first President warned that a “passionate attachment of one nation for another, produces a variety of evils.”

Sympathy for the favorite nation, facilitating the illusion of an imaginary common interest, in cases where no real common interest exists, and infusing into one the enmities of the other, betrays the former into a participation in the quarrels and wars of the latter, without adequate inducement or justification. It leads also to concessions to the favorite nation, of privileges denied to others, which is apt doubly to injure the  nation making the concessions; by unnecessarily parting with what ought to have been retained; and by exciting jealousy, ill-will, and a disposition to retaliate, in the parties from whom equal privileges are withheld.

nation making the concessions; by unnecessarily parting with what ought to have been retained; and by exciting jealousy, ill-will, and a disposition to retaliate, in the parties from whom equal privileges are withheld.

And it gives to ambitious, corrupted, or deluded citizens, (who devote themselves to the favorite nation,) facility to betray or sacrifice the interests of their own country, without odium, sometimes even with popularity; gilding, with the appearance of a virtuous sense of obligation, a commendable deference for public opinion, or a laudable zeal for public good, the base or foolish compliances of ambition, corruption, or infatuation.

P.A. Madison concludes that that there is no “better way to insure attachment to the country then to require the President to have inherited his American citizenship through his American father and not through a foreign father.” This is because, “Any child can be born anywhere in the country and removed by their father to be raised in his native country. The risks would be for the child to return in later life to reside in this country bringing with him foreign influences and intrigues.”

With confidence, P.A. Madison subscribes to the idea that a natural-born citizen of the United States can only mean, “those persons born whose father the United States already has an established jurisdiction over, i.e., born to father’s who are themselves citizens of the United States. A person who had been born under a double allegiance cannot be said to be a natural-born citizen of the United States because such status is not recognized (only in fiction of law). A child born to an American mother and alien father could be said to be a citizen of the United States by some affirmative act of law but never entitled to be a natural-born citizen because through laws of nature the child inherits the condition of their father.”

Would P.A. Madison’s logic hold up in court? Would the court system consider such reasoning when determining who is eligible to be President of the United States?

Common Knowledge would define a natural-born citizen as one who is a citizen by no act of law, or act of naturalization.

What is the difference between a citizen and a natural-born citizen?

Framer James Wilson said, “A citizen of the United States is he, who is a citizen of at least some one state in the Union.” These citizens of each State were united together through Article IV, Sec. II of the U.S. Constitution, and thus, no act of Congress was required to make citizens of the individual States citizens of the United States.

Jurisdiction over citizenship via birth within the several States was part of the “ordinary course of affairs” of the States that only local laws could affect. Early acts of Naturalization recognized the individual State Legislatures as the only authority who could make anyone a citizen of a State.

Congress was vested with the power to make uniform rules of naturalization in order to remove alien-age from those who were already born abroad (outside of the States) who had immigrated to any one of the individual States. Congress could declare children born abroad to fathers who were already a citizen of some State to be a citizen themselves. Naturalization only provides for the removal of alien-age and not for the creation of citizens within individual States.

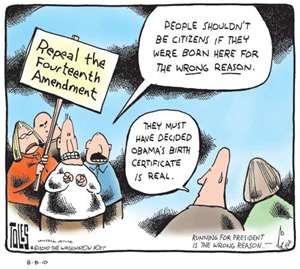

Fourteenth Amendment

The Fourteenth Amendment (1868) established that US citizenship is the primary citizenship in this country, and that state citizenship depends upon citizenship of the United States and the citizen’s place of residence. The States have no power to restrict their citizenship to any classes or persons.

The Fourteenth Amendment established a written national rule declaring who are citizens through birth or naturalization. According to the 14th  Amendment, “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.”

Amendment, “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.”

During the original debate over the amendment Senator Jacob M. Howard of Michigan — the author of the citizenship clause — described the clause as excluding not only Indians but “persons born in the United States who are foreigners, aliens, who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers.” Howard also stated the word jurisdiction meant the United States possessed a “full and complete jurisdiction” over the person described in the amendment. Such meaning precluded citizenship to any person who was beholden, in even the slightest respect, to any sovereignty other than a U.S. state or the federal government.

Thus, the status of natural born citizen is conditional upon being born “subject to the jurisdiction” of the United States — a condition not required under the common law. This national rule prevents us from interpreting natural-born citizen under common law rules because it eliminates the possibility of a child being born with more than one allegiance.

In conclusion, P.A. Madison draws attention to Rep. John A. Bingham’s (OH) comments about Section 1992 of the Revised Statutes. Rep. Bingham is the author behind the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

“Every human being born within the jurisdiction of the United States of parents not owing allegiance to any foreign sovereignty is, in the language of your Constitution itself, a natural born citizen.” (Cong. Globe, 39th, 1st Sess., 1291 (1866))

P.A. Madison provides context to Bingham’s definition.

Bingham subscribed to the same view as most everyone in Congress at the time that in order to be born a citizen of the United States one must be born within the allegiance of the Nation. To be born within the allegiance of the United States the parents, or more precisely, the father, must not owe allegiance to some other foreign sovereignty (remember the U.S. abandoned England’s “natural allegiance” doctrine). This of course, explains why emphasis of not owing allegiance to anyone else was the affect of being subject to the jurisdiction of the United States.

Defining a “natural born citizen”

The Courts have taken other ideas into consideration when determining who qualifies as a “natural born citizen.”

United States v. Wong Kim Ark (1898). On March 28, 1898, in delivering the opinion of the Supreme Court for United States v. Wong Kim Ark, in which the Supreme Court had to determine, “whether a child born in the United States, of parents of Chinese descent, who, at the time of his birth, are subjects of the Emperor of China, but have a permanent domicile and residence in the United States, and are there carrying on business, and  are not employed in any diplomatic or official capacity under the Emperor of China, becomes at the time of his birth a citizen of the United States by virtue of the first clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution,” Justice Gray stated, “In construing any act of legislation, whether a statute enacted by the legislature or a constitution established by the people as the supreme law of the land, regard is to be had not only to all parts of the act itself, and of any former act of the same lawmaking power of which the act in question is an amendment, but also to the condition and to the history [p654] of the law as previously existing, and in the light of which the new act must be read and interpreted.”

are not employed in any diplomatic or official capacity under the Emperor of China, becomes at the time of his birth a citizen of the United States by virtue of the first clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution,” Justice Gray stated, “In construing any act of legislation, whether a statute enacted by the legislature or a constitution established by the people as the supreme law of the land, regard is to be had not only to all parts of the act itself, and of any former act of the same lawmaking power of which the act in question is an amendment, but also to the condition and to the history [p654] of the law as previously existing, and in the light of which the new act must be read and interpreted.”

“The Constitution nowhere defines the meaning of these words, either by way of inclusion or of exclusion, except insofar as this is done by the affirmative declaration that ‘all persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States.’ In this as in other respects, it must be interpreted in the light of the common law, the principles and history of which were familiarly known to the framers of the Constitution.”

Justice Gray referred to several cases brought before the court which helped establish precedents for his decision, “This court is of opinion that the question must be answered in the affirmative.”

Justice Gray came to his decision based on the idea that birth and allegiance equal “natural born citizenship.” This idea was first promulgated in the common law. By example, he cites United several court cases, the first case here is representative of the reasoning leading to his conclusion.

United States v. Rhodes (1866) “In U. S. v. Rhodes (1866), Mr. Justice Swayne, sitting in the circuit court, said: ‘All persons born in the allegiance of the king are natural- born subjects, and all persons born in the allegiance of the United States are natural-born citizens. Birth and allegiance go together. Such is the rule of the common law, and it is the common law of this country, as well as of England.’ ‘We find no warrant for the opinion that this great principle of the common law has ever been changed in the United States. It has always obtained here with the same vigor, and subject only to the same exceptions, since as before the Revolution.’”

The fundamental principle of the common law with regard to English nationality was birth within the allegiance, also called “ligealty,” “obedience,” “faith,” or “power” of the King. The principle embraced all persons born within the King’s allegiance and subject to his protection. Such allegiance and protection were mutual — as expressed in the maxim “protectio trahit subjectionem, et subjectio protectionem” — and were not restricted to natural-born subjects and naturalized subjects, or to those who had taken an oath of allegiance, but were predicable of aliens in amity so long as they were within the kingdom. Children, born in England, of such aliens were therefore natural-born subjects. But the children, born within the realm, of foreign ambassadors, or the children of alien enemies, born during and within their hostile occupation of part of the King’s dominions, were not natural-born subjects because not born within the allegiance, the obedience, or the power, or, as would be said at this day, within the jurisdiction, of the King.

Minor v. Happersett (1875). In Minor v. Happersett, argued on February 9, 1875 and decided March 29, 1875, Chief Justice Waite delivered the opinion of the court, which included a definition of natural-born citizens based on the common-law at the time of the US Constitution’s passage and subsequent legislation. His opinion diverges slightly from Justice Swayne’s:

“The Constitution does not, in words, say who shall be natural-born citizens. Resort must be had elsewhere to ascertain that. At common-law, with the nomenclature of which the framers of the Constitution were familiar, it was never doubted that all children born in a country of parents who were its citizens became themselves, upon their birth, citizens also. These were natives, or natural-born citizens, as distinguished from aliens or foreigners. Some authorities go further and include as citizens children born within the jurisdiction without reference to the citizenship of their [p168] parents. As to this class there have been doubts, but never as to the first. For the purposes of this case it is not necessary to solve these doubts. It is sufficient for everything we have now to consider that all children born of citizen parents within the jurisdiction are themselves citizens.

Under the power to adopt a uniform system of naturalization Congress, as early as 1790, provided “that any alien, being a free white person,” might be admitted as a citizen of the United States, and that the children of such persons so naturalized, dwelling within the United States, being under twenty-one years of age at the time of such naturalization, should also be considered citizens of the United States, and that the children of citizens of the United States that might be born beyond the sea, or out of the limits of the United States, should be considered as natural-born citizens. [n8] These provisions thus enacted have, in substance, been retained in all the naturalization laws adopted since. In 1855, however, the last provision was somewhat extended, and all persons theretofore born or thereafter to be born out of the limits of the jurisdiction of the United States, whose fathers were, or should be at the time of their birth, citizens of the United States, were declared to be citizens also. [n9]

As early as 1804 it was enacted by Congress that when any alien who had declared his intention to become a citizen in the manner provided by law died before he was actually naturalized, his widow and children should be considered as citizens of the United States, and entitled to all rights and privileges as such upon taking the necessary oath; [n10] and in 1855 it was further provided that any woman who might lawfully be naturalized under the existing laws, married, or [p169] who should be married to a citizen of the United States, should be deemed and taken to be a citizen. [n11]

From this it is apparent that from the commencement of the legislation upon this subject alien women and alien minors could be made citizens by naturalization, and we think it will not be contended that this would have been done if it had not been supposed that native women and native minors were already citizens by birth.”

Dissenting Opinion in U.S. v. Wong Kim Ark (1898). Chief Justice Fuller objected to the idea that the only thing “natural born” ever meant in the first place was that the individual in question was born on U.S. soil: “[I]t is unreasonable to conclude that ‘natural born citizen’ applied to everybody born within the geographical tract known as the United States, irrespective of circumstances; and that the children of foreigners, happening to be born to them while passing through the country, whether of royal parentage or not, or whether of the Mongolian, Malay, or other race, were eligible to the presidency, while children of our citizens, born abroad, were not.”

At issue is whether or not a parent must be a citizen in order for a person born under the jurisdiction of the United States to be considered a “natural born citizen.” There were conflicting views, represented by the opinions and dissents of the courts and in writings reflective of the time period.

E. de Vattel’s Law of Nations (1758). “The natives, or natural-born citizens, are those born in the country, of parents who are citizens. As the society can not exist and perpetuate itself otherwise than by the children of the citizens, those children naturally follow the condition of their fathers, and succeed to all their rights. The society is supposed to desire this, in consequence of what it owes to its own preservation; and it is presumed, as a matter of course, that each citizen, on entering into society, reserves to his children the right of becoming members of it. The country of the fathers is therefore that of the children.”

Current definition

Here is where the definition of “natural born citizen” currently stands.

State Department Foreign Affairs Manual

• U.S. citizenship may be acquired either at birth or through naturalization.

• U.S. laws governing the acquisition of citizenship at birth embody two legal principles:

1. Jus soli (the law of the soil), a rule of common law under which the place of a person’s birth determines citizenship. In addition to common law, this principle is embodied in the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and the various U.S. citizenship and nationality statutes.

2. Jus sanguinis (the law of the bloodline ), a concept of Roman or civil law under which a person’s citizenship is determined by the citizenship of one or both parents. This rule, frequently called “citizenship by descent” or “derivative citizenship”, is not embodied in the U.S. Constitution, but such citizenship is granted through statute. As laws have changed, the requirements for conferring and retaining derivative citizenship have also changed.

• Naturalization is “the conferring of nationality of a state upon a person after birth, by any means whatsoever” or conferring of citizenship upon a person. Naturalization can be granted automatically or pursuant to an application. Under U.S. law, foreign naturalization acquired automatically is not an expatriating act.

U.S. Code definition

Title 8, Section 1401, of the U.S. Code provides the current definition for a natural-born citizen.

• Anyone born inside the United States and subject to the jurisdiction of the United States, which exempts the child of a diplomat from this provision

• Any Indian or Eskimo born in the United States, provided being a citizen of the U.S. does not impair the person’s status as a citizen of the tribe

• Any one born outside the United States, both of whose parents are citizens of the U.S., as long as one parent has lived in the U.S.

• Any one born outside the United States, if one parent is a citizen and lived in the U.S. for at least one year and the other parent is a U.S. national

• Any one born in a U.S. possession, if one parent is a citizen and lived in the U.S. for at least one year

• Any one found in the U.S. under the age of five, whose parentage cannot be determined, as long as proof of non-citizenship is not provided by age 21

• Any one born outside the United States, if one parent is an alien and as long as the other parent is a citizen of the U.S. who lived in the U.S. for at least five years (with military and diplomatic service included in this time)

Separate sections confer citizenship on persons living in US territories as of a certain date, and usually confer natural-born status on persons born in those territories after that date. Concerning the Panama Canal Zone and the nation of Panama, the law states that anyone born in the Canal Zone or in Panama itself, on or after February 26, 1904, to a mother and/or father who is a United States citizen, was “declared” to be a United States citizen. The terms “natural-born” or “citizen at birth” are missing from this section.

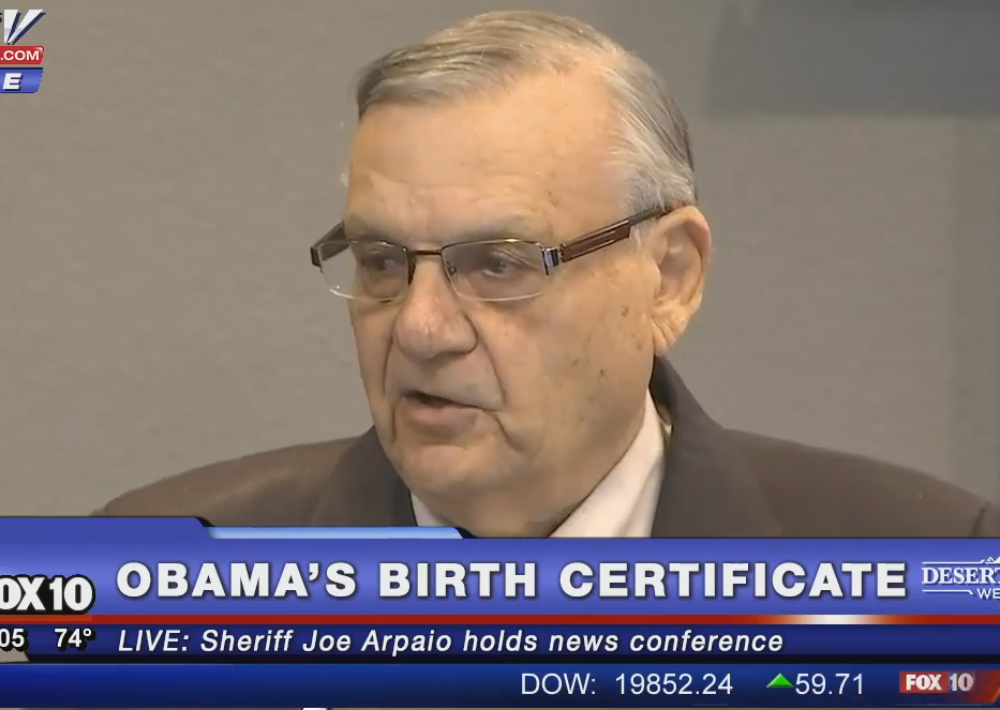

Although President Obama has a Kenyan father, the fact that his mother was a citizen should legitimize his being born a U.S. citizen. After his parents divorced, Obama’s mother remarried. Her second husband was an Indonesian national and, as a small child, Obama was moved to Indonesia with his mother and adopted father. Questions have been raised as to whether his citizenship was actually renounced. It is unlikely his birth certificate would indicate that he was born of some other lineage, however the certificate is sealed and the public does not have access to his  records. To preclude future controversies of this type, a more formal vetting process of citizenship qualifications should perhaps be established before the next cycle of elections.

records. To preclude future controversies of this type, a more formal vetting process of citizenship qualifications should perhaps be established before the next cycle of elections.

In 2004, a bill (S.2128) to define the term “natural born Citizen” as used in the Constitution of the United States to establish eligibility for the Office of President was introduced by Sen. Don Nickles and was cosponsored by Sen. James Inhofe and Sen. Mary Landrieu. The bill never became law.

In 2008, a resolution sponsored by Sen. Claire McCaskill and co-sponsored by Sen. Hillary Clinton, Sen. Thomas Coburn, Sen. Patrick Leahy, Sen. Barack Obama, and Sen. Jim Webb recognizing that John Sidney McCain, III, is a natural born citizen was introduced and passed Senate without amendment. This resolution stated that John Sidney McCain, III, is a “natural born Citizen” under Article II, Section 1, of the Constitution of the United States.

In 2008, when Arizona Senator John McCain ran for president, some theorized that because McCain was born in the Canal Zone, he was not actually qualified to be president. However, it can be argued that section 1403 applied to a small group of people to whom section 1401 did not apply. McCain is a natural-born citizen under 8 USC 1401(c): “a person born outside of the United States and its outlying possessions of parents both of whom are citizens of the United States and one of whom has had a residence in the United States or one of its outlying possessions, prior to the birth of such person.” Not everyone agrees that this section includes McCain — but absent a court ruling either way, the resolution stands..

The Supreme Court has held that there are only two ways to become a citizen:

1) birth in the United States, thus becoming a citizen under the citizenship clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, or

2) satisfaction of every requirement of a statute enacted by Congress granting citizenship to a class of people. The second category includes naturalization of individual adults or children already born; collective naturalization of groups, such as natives of territory acquired by the United States; and naturalization at birth of certain classes of children born abroad to citizens. Those born in the United States are uncontroversially natural born citizen, however Charles Gordon in “Who Can be President of the United States: The Unresolved Enigma” argues that those obtaining citizenship at birth by statute are natural born citizens. However, natural born citizenship can be acquired only at the moment of birth.

Wong Kim Ark thus recognizes four categories. A person can be:

1) both in the United States and subject to its jurisdiction, like a Chinese immigrant in California;

2) neither in the United States nor subject to its jurisdiction, like a Brazilian citizen in São Paulo;

3) in the United States but not subject to its jurisdiction, like a British soldier occupying Washington, D.C. during the War of 1812; or

4) out of the United States but subject to its jurisdiction, like a U.S. merchant on a guano island—one of the unclaimed, commercially valuable islands that Congress provided could be made U.S. territory upon application of a U.S. petitioner.

Only persons born in the first category are citizens by birth under the Fourteenth Amendment; only those born in the second category to U.S. citizens are covered by section 1993.

There is a need to have a definition of natural-born citizen that cannot be politicized. The definition must be protected from the politics of today and ensconced in the Constitution. Whether common law ideas or Vattel’s ideas prevail, we need to define what is to be acceptable in our Commander in Chief. All of the arguments made by the Framers regarding foreign influence must be taken into consideration because they knew then as we know now; the sovereignty of our great nation is at risk.